'The list is life'

#13 - 'Schindler's List'

In his “Great Movie” writeup of Schindler’s List, the legendary Roger Ebert says that the film is “described as … about the Holocaust, but the Holocaust supplies the field for the story, rather than the subject.”

The point Ebert is trying to make is an obvious but salient one: no filmmaker trying to appeal to the masses could set out to make a picture “about the Holocaust” and succeed. This is really true of any historical event or movement in which millions of lives are swept up and scattered about - the very future of humanity irrevocably changed as a result. And it is as much about the limits of our comprehension in a two- or three-hour sitting as anything else.

We need a hook, Ebert argues. We need something that will make such life- and world-altering events more digestible. And that hook, he rightly surmises, is the two characters at the heart of the film - Oskar Schindler, the seemingly reluctant war profiteer who winds up going to great lengths to save more than a thousand Polish Jews from near-certain death at Auschwitz, and Amon Goth, the psychopathic SS officer who unwittingly enables Schindler even as he forges an unending path of death and destruction in his direct wake.

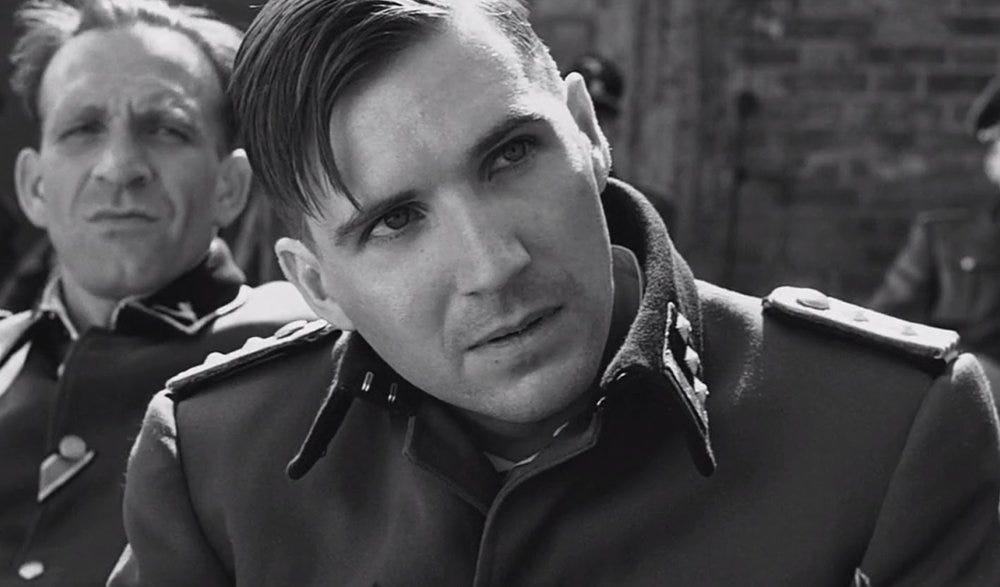

The pair, played by Liam Neeson and Ralph Fiennes, respectively, are certainly compelling.

Schindler is an enigmatic figure. The first 30 or so minutes of the film feel almost like part of a different story as he carouses with Nazi officials in the name of procuring cheap labor for his Krakow factory. There's a shallowness to his conspiracy. Watching in a post-Mad Men era, there’s a Don Draper-like quality to Schindler (or, more accurately, the other way around). Schindler doesn’t seem interested in much besides women and his own personal success, and he has plenty of disdain for both the government officials he must gladhand and for his own staff.

Neeson’s performance is such that Schindler’s transformation never feels like much of one at all because it is not really announced in any concrete way. There is never an epiphany. Schindler seems to do the right thing almost by happenstance, only seeming to realize the magnitude of what he’s doing when Itzhak Stern, the character played by Ben Kingsley, tells him that his “list is an absolute good.”

“The List is life,” he adds, punctuating the gravity of his act.

Goth, meanwhile, is such a lunatic that it becomes hard to actually see him within the frame of Nazism at times. He wears the SS uniform - skulls and all - and he carries out Nazi policy ruthlessly, from the liquidation of the ghetto in Krakow to the building of forced labor camps to the Final Solution. But he also undulates between anger and forced laughter and cold, merciless violence and lust so wildly that you begin to wonder if the SS consisted of men as crazy as him by necessity or if Goth was a special breed even within that framework.

Viewed as a pair, there is the bizarre fact that Neeson and Fiennes resemble each other. And there is their respective characters’ individual agency within a genocidal movement to consider. They are two sides of the same coin to some degree, and their actions prompt natural thinking about what you would do if this was happening all around you.

But I think focusing heavily on Schindler and Goth is too reductive, as is characterizing the Holocaust as simply the “field for the story” in this film. These two men are our eyes and ears, but what they witness is the Holocaust itself - perhaps not every life wrapped up in it, perhaps not every piece of the horrific descent toward industrialized death, but much of it indeed.

We know this because of the way Spielberg keeps his lens trained on the horror, with only brief reminders about who is either witnessing it (in the case of Schindler) or perpetrating it (in the case of Goth).

The liquidation of the Krakow ghetto is the best example of this in the film - Schindler witnesses it on horseback from an outcrop above the city - but the scenes, coming in relentless waves, with little dialogue, and shot in a shaky, hyper-realistic style, are such that you forget who is watching. There are many other moments like this, though, from Goth’s senseless murder of a boy who displeases him with a sniper rifle steps away from where Kingsley’s Stern walks to the terror of some of Schindler’s workers when they believe they are about to be gassed at Auschwitz and beyond.

Spielberg’s decision to shoot the film almost entirely in black and white is another hint that this film is much more than a dual character study. Black and white remains so much more powerful than color films. Its effect in this case makes the kind of photos you’d find in a history textbook come more fully to life. These images - the sounds and sights - can not so easily be flipped past.

And they should not be. Two decades after it was released, Schindler’s List feels more urgent than ever, due in no small part to a resurgence of anti-Semitism in the West, a horrifying humanitarian crisis in Syria, and an administration in this country that, viewed through even the most positive lens, seems to have fundamental gaps in its understanding of what Adolf Hitler's Third Reich actually did to the Jews of Europe.

Back to Spielberg: as great as he is, I would never describe his work as subtle in its messaging. But subtlety is not a requirement of great art, and if his primary legacy - as the man most responsible for ushering in the Blockbuster Era - leads some to underestimate his skills - both subtle and obvious - as an artist, well, then this is a film that simply can’t be ignored in that context.

Schindler’s List doesn’t have what I would describe as highly intellectual themes. Instead, it delivers messages that we are all taught in grade school with horrifying, traumatizing realism. Those who ignore or forget history are doomed to repeat it. Moral choices are rarely easy and often come with grave risk. Doing the wrong thing or accepting the wrong thing, even if it might seem small in that moment (as in an early scene when a Hasidic Jew is mocked for his personal appearance by German soldiers), can be part of a much larger, much graver wrong. The right choice by just one person can save thousands of lives.

School-aged wisdom bears minding in adulthood (again, especially in times like these), and there’s a difference between being taught something and learning or relearning it. Spielberg’s lessons, drilled home with finality in the film’s conclusion as real-life survivors from the List and their descendants stream past Schindler’s grave, like the rest of his work, are not subtle.

When they are this powerful and important, they needn’t be.