Netflix as event horizon

The tech company has long wanted to kill movie theaters. Now, it might have its chance.

Netflix does not want you to see movies in a theater. Despite its origin story, it does not particularly believe in movies or film or “the cinema.” It believes in “content” and “engagement,” just like every other company in Silicon Valley. It is, in other words, a technology company, not an entertainment company, which is to say that its aims and incentives are even more perverse than that of the average Fortune 500 firm.

This feels worth making a point of in the wake of last month’s news that Netflix is attempting to complete the purchase of Warner Brothers—the most Hollywood of all the Hollywood studios—for $82.7 billion.

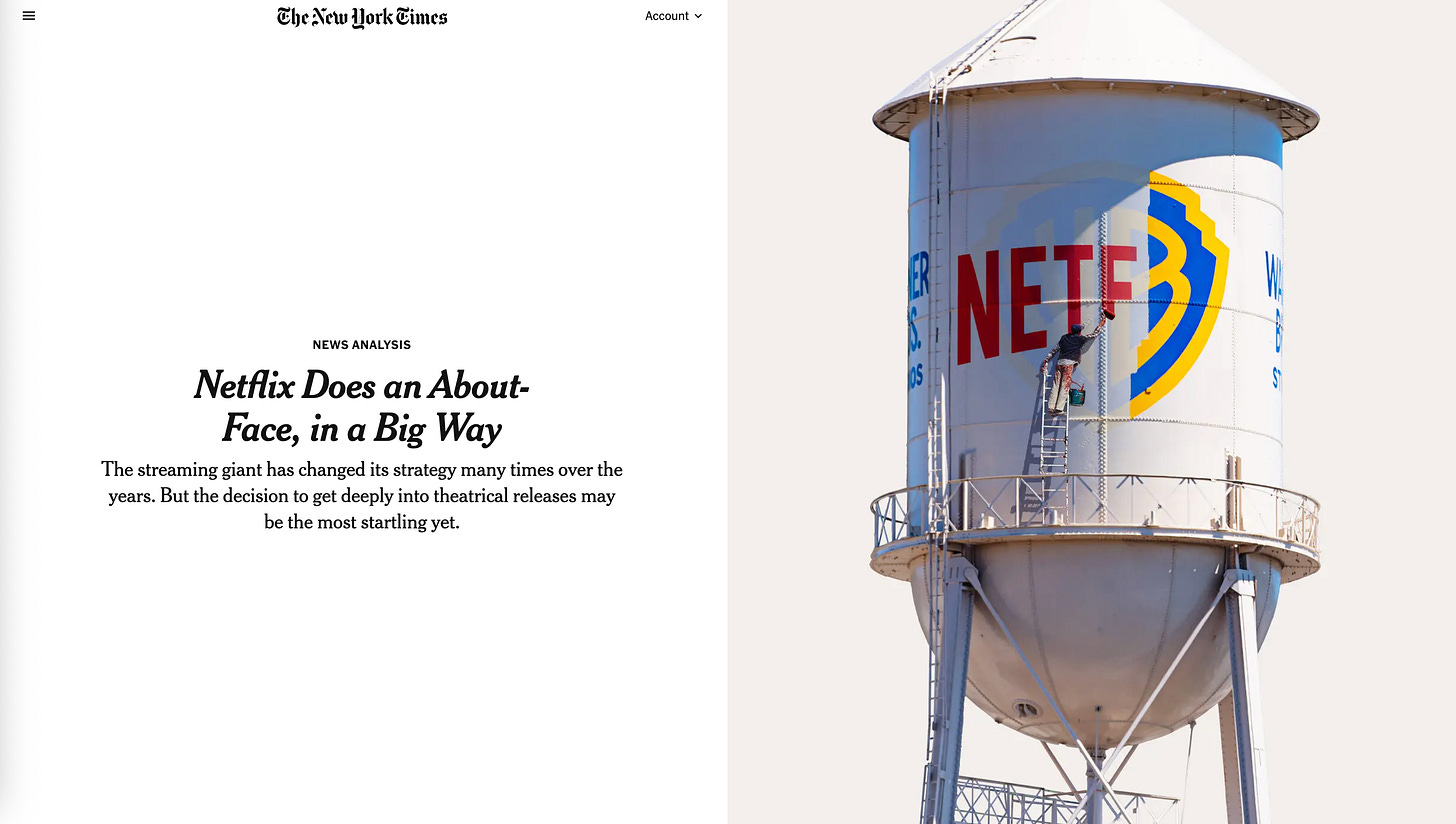

To be clear, it feels that way because the party line coming out of Netflix right now is that it won’t really mess with the WB operation, that, in fact, it might be Netflix coming around to the idea of theatrical distribution, just as it came around to the idea of cracking down on password sharing and incorporating advertising after saying it wouldn’t do those things for years. And this is a party line that is a huge part of the framing of the media coverage of this potential deal. Just take it from The New York Times …

In fairness to The Times, the analysis in the article I’ve screenshotted above ought to give its readers reasons for healthy skepticism:

In 2022, Ted Sarandos, a co-chief executive of Netflix, said, “We make our movies for our members, and we really want them to watch them on Netflix.”

In May of this year, he called theatrical distribution “an outmoded idea.”

And in October, Mr. Sarandos said on an earnings call that the company’s goal was to “give our members exclusive first-run movies on Netflix.”

Oh, well — never mind.

But the headline here, along with the context that is being emphasized throughout the article, is a choice in and of itself—one that places Netflix on the continuum of an emergently powerful entertainment company as opposed to what it is, an emergently powerful Silicon Valley outfit.

What if the primary context for this proposed merger was not that of a Hollywood upstart that has reversed course a few times but instead more akin to Facebook’s anti-competitive acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp? What if enshittification is the lens through which all of this is viewed?

Well, we’d rightly assume that Netflix’s executives are lying through their teeth—that they are telling us, consumers, regulators, everyone, what we want to hear so that they can lock us in to a platform that increases costs in lockstep with a degradation of quality.

So, let me just say what The New York Times can’t (or won’t): Netflix is either lying to us or, if not, letting consumers believe what they want to believe. They have made no—none, zero—firm commitments to do things any differently than today. If a press release saying that “it expects to maintain … current operations and build on its strengths, including theatrical releases for films,” counts as such, then you need to hear more lawyers discussing word choices.

We should take Ted Sarandos at his word, not the tortured, interrogated pablum of his legal department and public relations firm. He believes theaters are “outmoded.”

There is a possibility that the government bails us out. Paramount has lodged a competing, hostile takeover bid, and all three studios are bracing for lengthy fight before any potential deal is done.

Larry Ellison’s son, David, runs that studio, and the Ellisons are close with the Trump administration. Jared Kushner, the president’s son-in-law, is involved in the Paramount bid. Indeed, this is why many in the industry didn’t really see a successful Netflix bid coming.

Even if you set aside the Paramount bid and all the tangled relationships between Washington D.C. and Hollywood, there’s a very good antitrust case to be made, given that this would fold the biggest and third-biggest streaming service in to one.

You have to assume our laws still have teeth, of course, and then you have to make a successful argument about the nature of both companies, but the risk to the deal is substantial enough that there are smart people who think this takeover bid is more about “freezing” a competitor than it is about taking market share, and that it is a strategic misstep by Netflix.

It would be lovely for that to be the case, but we’re so far through the looking glass here that I have zero expectations that something so obviously illegal would be treated as such by the Department of Justice.

And, really, that legal intrigue is beside the point if you love the cinema. Hoping Paramount, with an assist from Daddy Trump, prevails is a poverty mindset, as this piece by The American Prospect outlines.

The oligarchs and Trump hangers-on coming together to try to bully their way into giving Warner Bros. to Paramount instead of Netflix have different designs but will fundamentally lead to the same outcome: ruining Hollywood. A merged Paramount and Warner Bros., with Jared Kushner and a bunch of Middle East sovereign wealth funds behind the scenes of the financing, simply wipes out one major Hollywood studio entirely, just like the sale of Fox assets to Disney. We can expect the same drastic impact on theaters that the Netflix acquisition will have. Paramount+ is the number five streamer, and while not immediately presenting as drastic a consolidation as the Netflix bid, it still reduces options for consumers for streaming and for producers for bids for their services. There’s nothing much better here, and then you add in the MAGA attempt to control information flow through corrupting news media.

By the way, both deals lead to the creation of more debt. The Paramount proposal is predicated on a $54 billion bank loan, and the Netflix bank loan is $59 billion. For decades, failed mergers have created a wall of debt for Warner Bros., and a new wall of debt is being built through yet another merger.

FOR SOME REASON, THE PERVASIVE REACTION to this bidding war between Netflix and Paramount has been to choose sides, based mainly on your political persuasion. A Netflix deal, liberals believe, at least doesn’t put CNN and CBS under the thumb of Trump allies. To conservatives, that’s the promise of a Paramount deal. And in the Trump era of politicization of antitrust, we hear about secret meetings between the president and Netflix or Paramount executives, and gauge our preferences accordingly.

Yet this blinkered way of thinking about the economy, this idea that we simply must tolerate more Hollywood consolidation, and the best we can hope for is something that aligns in some way with our political beliefs, is completely wrong. Functionally it’s wrong, because state attorneys general can choose to use the Clayton Act to challenge either of these mergers, and they would have good precedent to block this attempt at monopolization. What the Trump administration wants is immaterial to the opportunity state AGs have to scrutinize either a Netflix or Warner Bros. deal.

But more than that, it presumes that Warner Bros., a historic American company that is doing about as well as it ever has, simply must sell itself. This “there is no alternative” mindset, sold by Wall Street for 40 years, has warped our thinking. Especially if the cable channels are split off, Warner Bros. can be a profitable company, with no need to indulge its executives’ dreams of a quick payout.

We can do better than “the best possible consolidation under the circumstances,” if we can just imagine for a second an outcome where the M&A people lose for once.

Truth be told, unless you’re under the age of 12, it shouldn’t take any imagination to conjure up the world we want.

We simply have to remind ourselves what happens when tech companies “disrupt” anything, whether it be taxicabs, vacation rentals, food delivery, news, or interpersonal relationships. In the end, we the consumers pay more for an inferior facsimile of what we had before while the workers starve.

Or, we can remind ourselves of what it is like to walk in to a movie theater that is busy and well taken care of on opening night—what it’s like to be alone together in a darkened room as our senses are thrilled visually and aurally.

It is not so far of a journey—just to the other side of COVID for most of us—to remember a good, all-encompassing trip to the theater. Hell, go to the right theater now, get a ticket for Avatar: Fire and Ash or Marty Supreme, and you can remember what it was like today.

I suppose the question becomes what are we fighting for, and how do we fight for it. In my view, the answer, in the context of Netflix’s moves specifically, is the theatergoing experience as we know it. There are many other things under threat, not the least of which is the creative class that is responsible for one of America’s greatest artistic and cultural contributions to the world. But it is Netflix alone that represents an extinction-level threat to movie theaters. Just listen to their executives.

Be self-interested for a second. Think about what it’s like to see a great movie in a crowded theater with friends and strangers alike. Think about Paul Rudd’s experience below, of seeing Avengers: Infinity War at the premiere of the film and anticipating the reaction to that film’s big moment.

Then think about Ted Sarandos calling something like that “outmoded.”

There’s a fight to be had in the courts here, but most of us will be interested spectators as that plays out. We can hope that it works out in our favor and we can place a call or two to our elected representatives, but that’s about it.

But there’s also one to be had in the streets—the one where your local movie theater is. And there, we can all do a bit more, can’t we?

We can make a point of putting our butts in movie seats for all different kinds of films. As a bonus, we can shut off our phones and leave the close captioning off, since staring at your phone in a theater is still frowned upon, and the sound systems at your cineplex don’t have to compete with your dishwasher. It all might amount to swimming upstream, but the Barnes & Nobles of the world prove that downward trend lines don’t have to amount to fate.

Sharp analysis. The framing of this as just another Hollywood deal instead of a tech platform consolidation really misses what's at stake. I worked in exhibition for a bit and saw firsthand how streaming companies view theatrical windows as obstacles rather than value-adds. The comparison to Facebook acquiring Instagram is spot-on, tho people forget how those deals get sold as partnerships before the enshitification kicks in.