Cops and robbers

#37 - 'GoodFellas'

Goodfellas is such a propulsive film - so frenetic, each scene better than the last, its conclusion so virtuosic - that its beginnings can seem like a distant memory by the time Sid Vicious careens his way through “My Way.”

Real time has passed, as evidenced by Sid Vicious’ coarse version of a Frank Sinatra standard. Director Martin Scorsese’s meticulous selection and use of pop music marks the time and reflects the mood.

Indeed, the entire arc of the film is told by the music that accompanies it. Long gone are Tony Bennett and Bobby Darin and all the doo wop at the start. The warped, innocent optimism reflected in those tunes has been pushed aside by ever-deepening darkness and aggression. It culminates, fittingly, with Sid Vicious, a guy who could barely play an instrument, might have stabbed his girlfriend to death, and died from a heroin overdose at 21.

“And now it’s all over,” says Henry Hill mournfully, just moments before Vicious’ outro.

He has turned his back on his crew and entered the witness protection program. He has no choice, but there’s no doubt that if he did, he wouldn’t be helping the feds.

It’s an elegiac sentiment - one that is literal, bodies sure do pile up in Goodfellas, especially as it works toward its conclusion, and figurative, as Hill, primarily through voiceover, celebrates a life that he can not return to, but also one that never really was.

That’s the thing about the “life” in which Henry Hill immerses us. When it is introduced to him, and when he introduces it to us, it is articulated in the terms of a clear, strong moral code. Keep your head down, do your job, demonstrate your loyalty, and you’ll be taken care of by your crew. You can do anything you want, take anything you want, as long as you stick to the code.

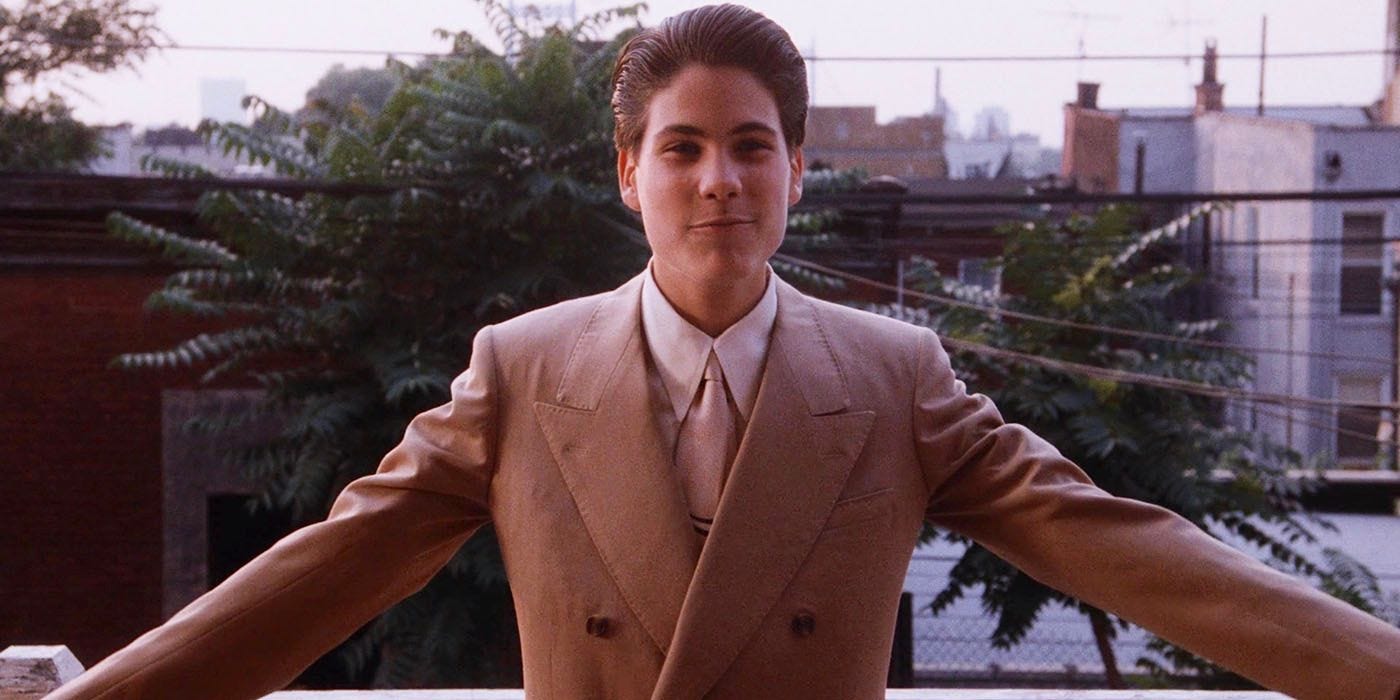

It’s no wonder that that has appeal to a wayward pre-teen growing up in a poor neighborhood. And it’s no wonder that, at his age, he has no idea earthly idea what he’s getting swept up in - that it will be far too late for him by the time he realizes he’s entered in to a Faustian bargain.

Indeed, there is a boyish fantasy at the heart of GoodFellas, as if a playground game of cops and robbers has been made real and Henry Hill is just making a choice about what team to join.

He’s indulged in the fantasy by his elders and his peers. They scold him when he wastes “good aprons” to aid a gunshot wound victim on the side of the street. And they rub his head affectionately after he’s “pinched” for the first time, completing a twisted but mandatory rite of passage for any wise guy: your first, but not last, brush with the criminal justice system.

As he walks out of the courthouse and collects pats on the back and affectionate slugs on the shoulder from his crew, Ray Liotta’s Hill voices over the two rules he learned: “Never rat on your friends, and always keep your mouth shut.”

There’s a stupid humor to this sentiment. To make a perhaps obvious point, this is actually one rule said two ways. More than that, though, there is foreboding. Everyone, including Henry Hill, will break this rule by the end of the film. And that is the real story of GoodFellas: a promise only a child would believe that a well-adjusted adult would immediately recognize as destined to be broken.

And so Scorsese uses every tool available to him to explain how a spell cast on a boy could last so deep in to adulthood. Yes, there is Liotta’s ever-present narration, his words rationalizing the depravity and immorality to which we are witness.

But it is the other senses that explain it better, starting with a camera that never stops moving. These men are always - always - in motion. That ceaseless activity takes them through the bowels of the Copacabana to a choice table, sure, but it also takes them to hastily dug (and exhumed) graves in the New Jersey forest. In between all that doo wop and Darin, there are always tires screeching, an aural reminder that there is no time to stop and think for Hill and Jimmy Conway (Robert De Niro) and Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) and all the rest.

Perhaps the most assaulting and memorable examples of this are the now meme-worthy moments of laughter and menace at one of the clubs where Henry and his crew hang out.

Drinks flow, cigarette smoke lingers in the air, and Pesci and Liotta and De Niro bust each other’s chops. They shout and curse and laughter erupts, but it is not the kind that seems remotely genuine. It is performative, exaggerated laughter, a sign that these characters might be fully grown, but that they’re still playing a schoolyard game.

There is a shabby reality to the mob life that Scorsese exposes with GoodFellas. The glamour of that walk through the Copacabana is belied by the humble homes, cheap clothes, and bad skin that is obvious in the daylight.

Just about every mob story - real or fictional - ends in the same way. There is a wave of destructive violence, and, for those who survive it, there is prison or a deal with the authorities that keeps you out of it, but then exposes you to the next wave of gunshots.

GoodFellas is no different in its beats. What sets it apart - besides the immense skill with which it is told - is that it is inward-looking. It is concerned specifically with the end-to-end fraudulence of “the life.” It gives Henry Hill free rein to rationalize his rampant sociopathy with his words, but undermines them at every turn with everything else on display.

The Godfather, to choose an obvious point of contrast, is about the struggle to break free of “the life” and realize the American Dream. Michael Corleone, and even his father Vito, are smart enough to understand how the story ends if their family can’t figure out a way to go straight.

This thought never seems to occur to Henry Hill or Jimmy or Tommy or anyone else in their orbit. It’s not clear whether they know they are on borrowed time or not, but it doesn’t seem like any of them would change their ways anyway, at least as long as they have a choice.